Long ago, the grandmother sits with the elders and smokes the medicine in the pipe. She is not even technically a grandmother, so much as a great- or great-great-grandmother, an almost mythic figure who, from the vantage of her granddaughter, blends in with the land itself. But in this memory, she is just a girl, one newly initiated in tribal practices and looking up to the elders. They are all of them women, the elders. They sit in a hut with a cylindrical top, through which their smoke kisses the sky, their faces aglow with the heat of a central fire.

In this time, the act of smoking the medicine serves as both a recognition of and prayer to something greater than oneself. The closest way for a modern person to understand it would be to say that the sky is alive, but even that is a reduction of the concept; the sky is conscious, is a being, is as much a member of the tribe as any one of the women sitting around the fire. Ditto the trees, the mountains, the animals hunted by the tribe as food. All these beings keep both expectations and assurances regarding the tribe, a sacred harmony that can as easily be disturbed as maintained. In this vision, the medicine is part of a complex system that ensures things remain as they are.

The grandmother feels held by her elders. The medicine inculcates a strange, wispy feeling in her body, but in a sense she knows that nothing is strange, because she walks a path that all elders have walked and that will deliver her their same status of elderhood, looking on as one younger than she is initiated in the ways. Everything is linked and synchronous, in this world—from the rain, to the desert spells of dryness, to the members of her tribe themselves, each of them doing exactly what they are supposed to do in each particular moment. To a modern, this manner of being might best be described as a “click.”

There is a change, though, over generations and with the coming of people not familiar with the ancestral ways. With these people, there are violence, subjugation, and misunderstanding, and some of the grandmother’s sisters choose to leave the tribe because they are promised lives of greater material ease. They will no longer need to pray for rain, if they join this new and foreign tribe; they can simply collect and funnel it as their needs require, and the same applies to all sorts of resources like meat, grain, clothing. With this quality of hoarding, one never has to worry about an unslaked hunger or unquenched thirst.

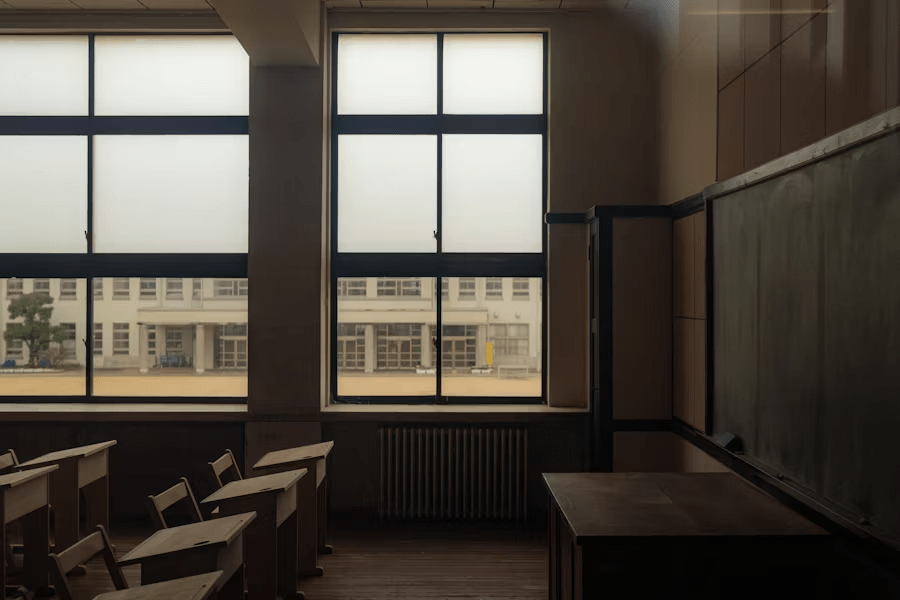

Other tribe members leave because they are forced to, and this is true of the grandmother’s own daughter, taken away from her and sent to a mechanical school in which she is indoctrinated with foreign ways. The grandmother’s heart breaks with this event; she does not reach elderhood in the way she envisioned, because in order to become an elder one must inspire the youth, and the grandmother is followed by no more children of her lineage, none on whom she can bestow her wisdom. In a sense, she is the first member of her family to die alone, unrealized.

Generations later, the plant medicine in which the grandmother once imbibed is spread across the land, taken away from the shadows of alleyways, vehicular backseats, the indentations of couches and thrust into boutique stores, soft music canceling out silence and well-garbed employees beaming professional smiles. In this reality, the grandmother’s granddaughter—not her literal granddaughter but one separated by many more generations—ceases purchasing weed from her dealer and instead gets it from a dispensary.

There is always an emptiness to this granddaughter’s use of the medicine. In fact, the emptiness is there whether she uses the medicine or not. When she drives to her job, and sees all the other people driving to their own jobs, the vast majority alone and all of them encased in glass walls like fish within aquaria, she feels the emptiness. She feels it at the job itself, certainly satisfying a need in that she is acquiring money with which to feed herself, but nevertheless unable to answer the fundamental question, “Why am I doing this?” She feels it when she talks on the phone with her mother, who lives in a different state and who always seems distracted by something unnamed—perhaps this is amplified by the pharmaceuticals the granddaughter’s mother has been prescribed since the granddaughter was a child—and when the granddaughter spends time with her own friends, many of whom smoke the medicine but none of whom believe in an aliveness to the sky, to the trees, to the animals they consume from drive-throughs. Who among them has even glimpsed the sky clearly enough to inquire as to whether it might be alive, occluded as it is by smoke of a different order?

From the emptiness, there are some who flirt with sobriety as a new form of medicine. Perhaps they wish they could share with others the experience the grandmother once had involving the plant variety, although few of them are aware of the history which robbed them of this experience, the necessity of that experience’s sedimentation in an animistic, reciprocal world. After all, ritual requires familiarity, requires shared history; by the time of the boutique stores and the everyday commute, these qualities have long been sloughed off, driven into the ground by a thudding machinery.

Sobriety enables a cleansing, but it does not rid one of the emptiness. For that, true community is needed, and one must learn to regard their brethren as kin. And for that, perhaps the starting point is to recognize that indeed there is a shared history, the fact that we are all of us birthed bewildered into a strange world, shorn of whatever once united us and asking, “Where has my grandmother gone?”

I love this piece… powerful and emotional, I have read it twice now

It makes me ache for the health of our grandmother earth

It makes me ache for the healing ways of my granmother

It makes me ache for the grandmothers you never met…

LikeLike