Before beginning his story, my 10th grade English teacher lowers the blinds and dims the lights. On retrospection years later, I will recognize this process as what is called “setting the stage,” segmenting a sensory environment so that when these stories occur, I and my classmates will feel privileged and therefore not spill the beans. In other words, the lowering of the blinds and dimming of the lights are meant to make us feel special.

In the story, my 10th grade English teacher is a college fraternity brother and he and his friends engage in what he dubs “hogging:” soliciting overweight women to have sex with them while fellow brothers film the encounter. On this particular occasion, my English teacher’s laughter spoils his location in the closet with a camera and the victim—an overweight college female—runs to the window to discover his brothers watching from a nearby hill, turning tails and fleeing. Unmentioned in my English teacher’s telling is the woman’s shame, which must have been unbelievable.

There were other stories like this, escapades from my English teacher’s glory days, but this is the one I most strongly remember. In exchange for “good” deeds such as holding an engaged discussion for a set amount of time, the English teacher would truck out one of the stories, prior to which there would always be the aforementioned setting of the stage.

It was a surprise to nobody when, the summer after I exited 10th grade, this same teacher was expelled from the school community for sleeping with students. As it turned out, each year he would pick and groom one female, and he would have sex with that female usually during her senior year. Partying with some seniors who had just graduated and supplying the alcohol himself, my 10th grade English teacher had left his name on the keg—meaning it was still there and thus incriminated him when police arrived. Without noteworthy fanfare from my high school, he was gone, and few of us who had taken his class ever heard from him again.

In a sense, my 10th grade English teacher was only enacting a fantasy I believe is universal: that of returning to an earlier phase of life, dominating that phase with present consciousness. Since he was decades our senior and had experienced things such as drugs and sex, my English teacher was able to easily pose as the coolest kid in class, and he used this status both to become a privileged ear and to gain access to budding women. I remember an occasion in which I and friends had been propositioned by several females in our class to strip for us, and we had said “no,” and this story had made its way back to the teacher through the channels he had established. In class, he shamed me and my friends for the story, telling us he hadn’t heard “no” before from guys who were “getting so little action.” Through the inlet to a clandestine, adult world into which he had fashioned himself, my 10th grade English teacher simultaneously acted as our gateway to cool.

Too, there is a way in which the teacher achieved something after which many adults strive: keeping in touch with his inner child. While he was in his forties at the time I knew him, this English teacher felt much younger—our peer if not our nearby senior—and he maintained “in” jokes with students that most teachers cannot. At one point, I remember the teacher paying several of us a dollar each to carry an obnoxious student out of the classroom by force, and each of us hoisted an arm or leg, dropped the student’s struggling body outside the door, and we shut the door while he protested. From a certain vantage, the classroom was an alternate world in which we could play, freely experiment with ourselves.

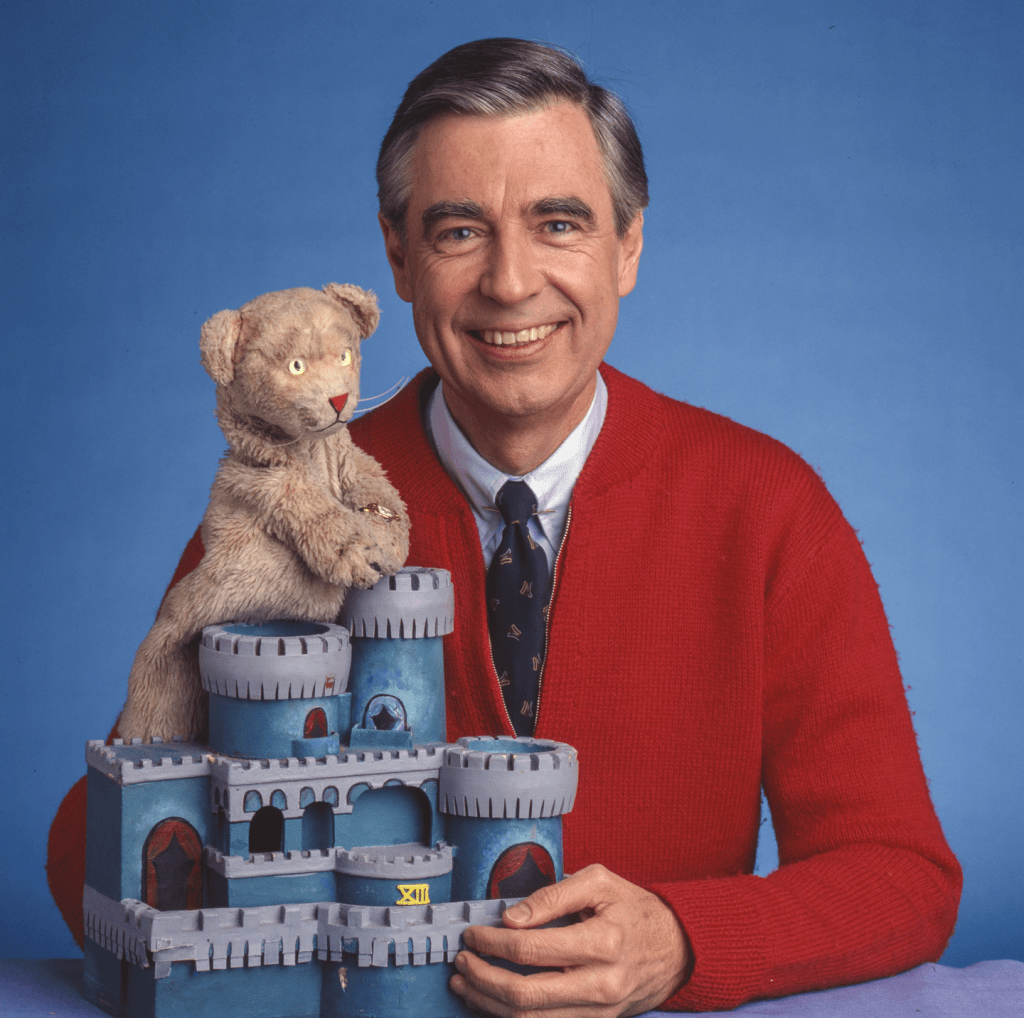

And yet a closer look will reveal that my 10th grade English teacher was not, in fact, noble in any respect. While he did realize a common fantasy of traveling “back in time” with present skills, he did so for an ulterior motive; and while he was in touch with an earlier self of his, it was not his inner child, but rather the adolescent forces that had chased that child offstage. These rebuttals are significant because they highlight the perversion inherent in pedophilia, and they can be illuminated through contrasting my English teacher with a saintlike servant of children such as Fred Rogers.

Like my English teacher, both in interviews and on his TV program Fred Rogers came across as a man who had not lost touch with his earlier, childlike self. Rogers played with puppets, constructed imaginative worlds with children, and sang songs with simple, Dr. Seussian lyrics. As the TV personality’s wife says of him in the fabulous documentary “Won’t You Be My Neighbor,” Rogers never forgot what it felt like to be small and vulnerable as a child.

And yet Rogers did not make these exchanges with children for his own reasons, but rather to serve the children themselves. In a soliloquy anyone who grew up with the icon will remember, Rogers ended his program each day by assuring the viewer that they had “made this day a special one” just by being themselves, that there was “no one quite like” them in the world. Literally separated by a TV screen from the subject of his discourse, there was nothing he could gain from making this charitable, empathic speech, and yet he did so for decades. Through these words alone, Rogers no doubt buoyed the confidence of millions of children.

Furthermore, unlike my English teacher, the part of himself on which Rogers drew was, in fact, his inner child. Throughout his show, he conjured up a panoply of states of being such as wonder, vulnerability, and imagination, states native to any child still learning to navigate the world. While my English teacher found similar routes of connection with 10th graders, he appealed to that part of us which in fact had squashed and begun to conceal our inner child, the adolescent part which worried about things like attention, status, and simulating ennui. While Rogers had faced the travails of adulthood and somehow managed to let his inner child shine through, my 10th grade English teacher had succumbed to obfuscation, emanating and falling prey to a false self.

These comparisons are formative to my own life as a teacher, where already I have been branded as “cool” and therefore accessible to students. Like my 10th grade English teacher, I am closer in age to my students than the average teacher, one in whom they can see themselves, one who still shares a degree of pop culture references. To some of the female students, I am no doubt attractive, and that option would be there were I to corrupt their trust in the way my 10th grade English teacher did ours. And yet unlike my English teacher, I recognize that any transaction that takes place between me and students must be for their benefit, since teaching in itself is a sacred obligation. There is nothing I can take from my students without paying great cost myself; such a blasphemy would be a mark against my soul. Furthermore, if there is a part of me which is to be most prized and communicated to students, it is not the part that makes them deem me cool; it is the part that renders me naïve, soft, cockamamie or aloof, the strange, hidden self that once felt threatened by my 10th grade English teacher. In other words, it is the part of me much younger than fifteen years old, and simultaneously in a manner timeless.