An earlier version of this story was published by Sixfold Magazine in the winter 2024 issue, available here.

For moments now Jeff has entertained the fantasy that he will secure himself an entire row, two empty seats beside him along which he can stretch, lie, even sleep. Perhaps it is the tattoos on his face which have kept the flight’s remaining passengers at bay. As usual.

But now there is one final passenger entering the plane, and that passenger is a monk, folds of his orange robe clutched in one hand and a small backpack around his free shoulder.

Should Jeff look out the window, feign indifference? Does one need a moment’s acknowledgement in order to acquire a seatmate, and will severing this possibility protect Jeff? Or should he look dead ahead at the monk, manufacturing a twitch in the eye, displaying his facial tattoos in their fullness? In the end, Jeff makes the mistake of glancing at the monk and smiling, and the monk bows and smiles in return, places his bag in the overhead compartment above Jeff’s row, sits. So the two will accompany each other during these five hours to California from Hawaii.

Jeff had been here for a friend’s wedding, during which he had suffered alienation from his high school crowd. The friend getting married had been the last in their group to do so—beside Jeff, that is—and many in the coterie had brought along spouses, even children. To stanch his discombobulation, Jeff had hit the bar early and hard, becoming encased in the glassy shell which dulls him to such feelings.

“Returning home or leaving home?” the monk asks Jeff. English does not seem to be his first language, but his voice is intentional and clear. His voice is also high, like the electric hum discernible in most houses if one really listens.

“Oh, uh, returning,” Jeff says. He would like not to continue this conversation beyond formalities.

“Where do you live?” the monk asks. His eyes are bright, beaming. With his hands now resting in his lap and his posture turned slightly toward Jeff, he looks as though there is nothing in the universe he would rather be doing.

“Denver,” Jeff says. Flashes come to him of the life to which he is returning, and he shivers and presses the flight attendant button above his head. When a physical attendant arrives, he will order the first of several rum/cokes—he hopes that such a person arrives soon.

“Ah, Denver, nice place,” says the monk. “I used to live there in my twenties.”

“Oh, yeah?” Jeff says. “Where do you live now?”

“Utah,” says the monk. “More quiet.”

“Uh huh,” says Jeff. The flight attendant arrives and he orders his drink, which he is promised will be delivered as soon as the flight has taken off; additionally, the attendant obliges his request for a double. As he orders, he tries to smile sincerely and to telegraph normalcy, but he imagines that smile from without, can perceive it bent and misshapen, something aflutter behind his eyes.

Throughout this exchange, the monk’s gaze is down, across folded hands and between his knees.

As the plane taxis from the gate the monk speaks again.

“What do you do for work?” he asks Jeff.

So there it is, the age-old question. Jeff could lie or relay a euphemism, as he has done a million times. Or he could describe his profession graphically, perhaps scaring the monk into switching seats at this late juncture. Inwardly, Jeff laughs at that possibility. But recently Jeff had been listening to a Buddhist influencer on YouTube, and the person had been speaking of the significance of truth-telling to setting us free; if he tells small truths, perhaps incrementally Jeff can spring himself from the razor-wire prison his life has become.

“I’m a content producer,” says Jeff. As he has done before, he raises his eyebrows and pantomimes scare quotes while saying this, hoping to confer a double meaning.

“Oh, what kind of content?” says the monk. He hasn’t understood.

“Um,” Jeff says. “There are certain… websites… online, where people go when they are feeling lonely. And there is something they watch… that is usually done in private. You know what I mean?”

The monk now nods sharply, visibly wincing.

Jeff completes his confession: “I make that content.”

There is a moment of the quiet toward which the monk gestured earlier, though this time punctuated by the voice of the pilot informing the passengers they will now be departing. The plane begins moving forward and gains speed, there is an instant of jerk, the front of the plane tilts into the air and the back reluctantly follows. The plane’s artificial atmosphere becomes more pressurized, more evident. Jeff prays that cruising altitude is low and hence he will soon be imbibing rum.

“So, you… How did you get into this way of life?” the monk asks Jeff.

Hm, that is a good question. It had been gradual, Jeff supposes. First of all, he had lost his virginity at thirteen, and he had started smoking weed and drinking alcohol around the same age. A prominent politician, his father had scarcely been home, and Jeff and his brothers had mostly had the house to themselves—their mother had been chronically ill. It hadn’t been long after he lost his virginity that Jeff and his first girlfriend had started making videos.

“Oh, everyone in my family has a knack for business,” he says. “This line of work is just mine.”

The plane has leveled off and the attendant rushes Jeff his drink prior to taking everyone else’s orders, almost as though applying a tourniquet to a bleeding soldier. Again Jeff tries to project an air of normalcy, again feels something deep within him waver. The flight attendant passes him a device and he pays using his card.

After the attendant leaves the monk turns to Jeff, having had time to ponder a new question. “Are you happy?” he says.

“Um, no,” says Jeff. His answer surprises him, as well as its instantaneity. Months ago he would have rationalized that he was doing great, centering on the amount of money pouring into his bank account. But again, now there is the precedent of the online influencer who beseeched Jeff to tell the truth, and here he is drinking hard liquor at the outset of a midmorning flight. So no, not especially brimming with happiness.

“Then why?” asks the monk. In his lap, his hands open and close.

Jeff thinks on this. With each sip of his drink, a warmth fills him, the familiar glass walls closing in. He is now enjoying answering the questions, but only because unconsciousness beckons, a light at the end of a tunnel.

“I suppose a long time ago I just started doing what feels good,” says Jeff. “Home didn’t feel so good. At first it felt better to drink and do drugs, to have sex with women, then to make money… but gradually what at first felt good, started feeling like hell. And I needed more and more of what felt good to forget the hell, like a painkiller.”

“Samsara,” says the monk.

“Hm?” asks Jeff. He steals another sip of the drink, a film coming over his eyes.

“It is our term for the world of illusion, the world of striving,” says the monk. “In this world, we become as hungry ghosts, never satiated because we are always grasping. It is a terrible existence.”

“Mhm,” says Jeff. In a moment he won’t care.

“How can you escape from this world?” the monk asks.

“Hm? I don’t know,” says Jeff. He has finished his drink now. “It’s alright. I mean, I make a crazy amount of money, so I’m able to support myself and have anything I want. And my girlfriend and I—my main girl—we’ll get married and have kids at some point, so we can still have a normal life. There’s no problem.” The film having enrobed him completely, Jeff nearly believes himself. That woman he encountered online said to tell the truth whenever one could or something like that. Sure, but the truth differs depending upon how many drinks Jeff has had and how recently.

“Oh,” says the monk. For the first time he looks off into the cabin, disappointed.

“Really, there’s no problem,” Jeff says. “I wouldn’t worry about me.” He catches the monk’s gaze again and, as with the attendant, attempts a verisimilitude of reassurance, but this time he’s lost the barometer for whether or not the presentation is false.

“I am glad to hear that,” says the monk. Again there is a pregnant blink of the eyes.

Jeff leans back in his seat, drifts off, wakes up anywhere from a half hour to several hours later. At this point his alcoholic film has dissipated, and again he perceives the plane’s cabin as though a baby, his skin infinitely tender and his senses drinking up each detail. There is a raciness within him, but simultaneously a love and curiosity.

Groggily he turns to the monk, who has refrained from distraction this whole time and is simply staring downward, through steepled hands.

“What about you?” asks Jeff.

“Hm?” says the monk. The same brightness, alertness in his eyes.

“What do you do for work?”

“Oh!” the monk chuckles. With his hands he indicates his garment, his bald head. “You’re looking at it,” he says.

“And how do you… How do you make money?” Jeff asks.

“Oh, money is not important,” says the monk. “It doesn’t take much to live, really. I used to be very concerned with money, like you. But when you live as a monk, numerous people rise up to support you with donations.”

Something in this soliloquy disquiets Jeff, and again he searches for and hits the flight attendant button, calling to himself another warming supplication. “Uh, that’s great,” he says, half to the monk, half to himself.

“You know, it is okay to feel sad,” says the monk. His hands are still steepled near his genitals, but his gaze is entirely leveled toward Jeff, his eyes beaming their kind crispness.

“Hm?” says Jeff.

“When I asked if you were happy earlier, you said no,” says the monk, “And anyway, I could have inferred that even if you yourself had not told me. Your tattoos told me. Your eyes told me. The speed with which you ordered a drink. Each time you feel uncomfortable, it seems as though you order a drink, wrap yourself in gauze, seek to numb the feeling. But it is okay just to feel it.”

Jeff nods at the monk. Now that he knows there is another rum/coke on the way, it is easier to assent to such a sentiment, easier to play equanimity. You know, there is someone the monk reminds Jeff of, someone of whom he hasn’t thought in a very long time. “Why are you telling me this?” Jeff asks.

“In a way, this is my work,” the monk responds, and once more his hands open and close, as though to communicate he has no choice.

The flight attendant is there earlier than before, this time already ferrying the rum/coke and supplemental shot on a tray. So she knows who Jeff is, recognizes the hungry ghost in him that must be fed. As he completes the transaction and performs his queasy smile, Jeff remembers that it is his grandmother of whom the monk reminds him, the gentle, steadying love with which she had presented Jeff and his brothers. There had always been a sense that they could do no wrong, with grandma. Even if she disagreed with some of their choices, that did not mean that they were bad people—more often, it meant that they were doing something which would harm themselves, an inclination which hurt her heart. Jeff feels a quiver in his own chest, and as he retracts from the flight attendant a single tear escapes his eye.

“Are you alright?” the monk asks.

“Yes, yes I’m fine,” Jeff says. He wipes at the eye with a free hand, positions his drink along his tray table. “Say, where you are going… Is it just a group of monks who meditate together, or is there one of you who is the leader, like a guru?”

“Everyone needs a guru,” responds the monk. “We can none of us do this work alone.” At the words “this work” he gestures in 360 degrees around the plane, suggesting what Jeff does not know.

“Um, there is someone I found on YouTube a while back,” Jeff says. He takes a sip of his drink, clears his throat against the bitterness. “Esther or Ezra… Esther Halcomb?”

The monk’s face is full of radiance and surprise. “That is my teacher!” he almost shouts. “I will be with her this evening!”

Jeff takes another sip of his drink, and the fact seems less salient already than it did a moment ago. “When you see her, will you… Do you just meditate together, or does she sort of tell you how to live your life?”

“It is not so much a matter of telling as it is of guiding,” the monk says. “We bring problems to her, she facilitates our finding our own solutions. But yes, there is also much meditating together, and we join in simple work tasks. Why do you ask?”

“I don’t like anyone telling me what to do with my life, is all,” Jeff says.

There is zero conversation during the subsequent hour of the flight, during which time Jeff faces forward and ruminates on the life to which he is returning. Again his drink steels him, manufacturing a tunnel in which he can be alone with these thoughts, the thoughts themselves somehow soupy. There is the girlfriend about whom Jeff told the monk, the one he intends to marry. Sure, she has to sleep with other people as part of their work—so does he—but that doesn’t mean she doesn’t love him, and sometimes, an ounce or ooze of that special love is even caught on camera. And there is Jeff’s liver, which stings now as he sips his drink, and which a doctor had called compromised following an ultrasound Jeff got at request of his girlfriend—somehow or other he will deal with that.

At this point the pilot informs the passengers that the plane has begun its descent, so Jeff must have been asleep a lot longer than he believed.

Hitting the flight attendant button one more time so that he can dispose of his garbage—or get another drink?—Jeff asks a further question of his seatmate: “So, how did you become a monk?”

The monk reflects on this, poised in repose. “A bit like you,” he finally says. “I used to party a lot, work hard, make good money. I wanted to be successful, even famous. But I found that the more I pursued these things, the emptier I became inside, and the more of any one of them it seemed I needed to stave off that emptiness. Eventually I found meditation, and I realized there was a kind of bliss available right here that did not necessitate fame, money—even the company of a woman.” He smiles at Jeff.

“But how do you…” Jeff twirls his empty glass. “How do you remain steady on this path? It seems to me there are pitfalls everywhere, that falling down is immeasurably likelier than holding true.”

“Well, we do fall down sometimes,” the monk says. “That is okay.”

Again Jeff is reminded of his grandmother—she had died when he was six years old, leaving him with the absence and ambition of his father, his mother’s frailty.

“What is your name?” Jeff finally asks the monk.

“Carmine,” the monk says. He and Jeff shake hands, and Jeff is struck by Carmine’s hands’ softness, their pliability.

So that is what hands feel like when they are not marred by grittiness, by worry, Jeff thinks. The flight attendant swoops in and he does order a final drink, a Hail Mary as the plane glides earthward.

*

After landing and taxiing, Carmine stands, bows again to Jeff, retrieves the bag he had initially placed in the overhead compartment and drapes it over his shoulder. He had done well with his seatmate, Carmine thinks. As Esther has modeled for him, there were moments of compassion that appeared to pierce Jeff’s shell, demonstrating to him the possibility of a lighter way of living. Even if Jeff had been unable to actualize these possibilities at this time, perhaps they will germinate, grow strong inside him.

Carmine waves off Jeff as they part ways inside the airport. Somehow, perhaps through the vehicle of intuition, he knows that his seatmate will abscond to a bar here, will spend his layover blanketing himself in alcohol such that he does not feel his pain. When he has another moment, Carmine will submit a formal prayer for Jeff, will ask for his soul’s alleviation of this curse.

For now, though, Carmine needs to hurry to his second flight, which he makes with only minutes to spare. Even monks need to rush about sometimes, he thinks, his sweat sealing the robe to his skin as he enters the plane.

Carmine’s second flight is less eventful than the first, no seatmate beside him and instead only the serene crackle of pressure-controlled air, the whistle of altitude. During this flight, he closes his eyes and, as Jeff did earlier, reflects upon the life to which he now returns. Like Jeff’s, it is a sort of prison, but unlike Jeff’s Carmine does not experience that prison as wrapped in razor wire. Instead, Carmine’s is a prison of mist or clouds, one freely chosen and simultaneously existing solely in his mind. At any time, Carmine could elect to leave the monastery, but why would he do so? His life may be more limited than Jeff’s, but by the same stroke it is more manageable.

As Carmine’s final flight crests into the Salt Lake airport, he flutters his eyes open, prepares to retrieve his bag and, this time, walk—not hurry—to the taxi which will bring him home.

An hour later Carmine arrives at the monastery, where already night has fallen and the monks have gone to bed. In her private quarters Esther Halcomb will be asleep, or perhaps reading literature as she often does in the evenings, equipping herself with references for her sermons. The dishes will have been washed and put away, the floor of the zendo swept, the gardens weeded for another morning’s watering. In all respects, the monastery simulates a well-oiled machine, one in which each monk acts as a single, happily abiding cog.

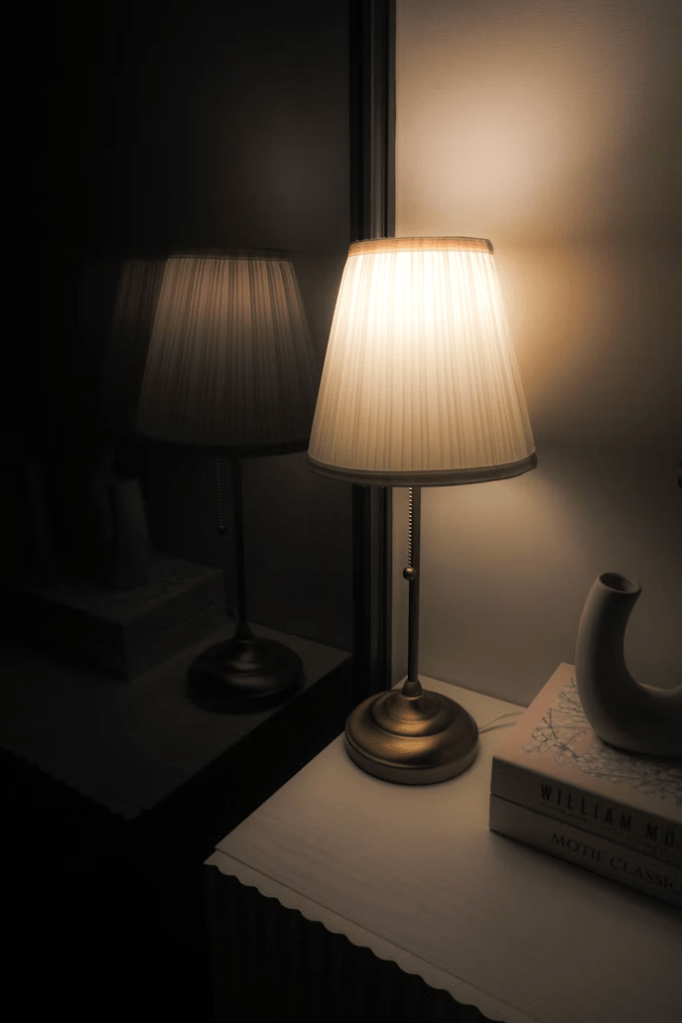

Within the quiet of his own room, Carmine sets down his bag, undresses from and places his robes in his hamper, then—wearing merely his underwear—peels back and slips inside his sheets. An incandescent, bedside light encircling him, he clicks on his phone’s WiFi and, as he has found himself doing ever since he was a teenage boy, accesses some porn that he might masturbate and seamlessly turn to dreaming.

There is a couple whose page Carmine has been visiting these recent months. US-based, with a kind of love between them that he had thought reserved for people who did not film and share their encounters. Viewing this alchemy, it is as though Carmine has broken through some holy law, observing the private in public and thereby assuaging his loneliness. The dichotomy makes him feel as though he is a very small boy being cradled by a giant mother, except that mother’s love is known only through refraction and voyeurism, as though Carmine looks onto the scene through a periscope or keyhole.

His penis already in his hand, he opens up a video on this couple’s page, but… A feeling of dread rushes through him. Unlike in their typical video, in this one the couple has positioned themselves against a mirror, so that through the mirror’s reflection Carmine can see the couple’s male, usually the videographer but not the subject. And he… Even behind and around the camera which the male holds as he thrusts into his beloved—or his business partner, or whatever—Carmine can make out a system of tattoos, one with which he familiarized himself just earlier today because… The videographer in the mirror is Jeff.

Carmine clicks off and sets the phone on his bedside table, face down. His penis still lies in his hand, but now flaccid, masturbation no longer an option nor a thought. As he had intimated with Jeff early on in their time together, Carmine experiences a flood of the kind of silence which is his life’s practice and direction, except that now that silence feels colored with voices, a deluge of chatter and syncopation, a locust swarm of hungry ghosts.

So Carmine was not merely Jeff’s guru, just as Esther is not merely Carmine’s. And Jeff was not the only hungry ghost sitting in his and Carmine’s row, not the only seatmate swaddled in something from which he could not wrest himself, certainly not alone.

The yellow light bathes Carmine in some truth from which he has hidden his whole life. For a long time before sleeping he sits in this light and ponders things, his hands forming a diamond around his penis but not bothering with it, allowing the organ to lie there dormant. It does not matter if Carmine is not well slept when he arises early tomorrow morning for meditation, he thinks; what matters is that he feel exactly this, in this moment, take in this synchronicity and not forget.

I really appreciated the earlier draft of this story.

I like the revision even more.

Really well written!

LikeLiked by 1 person