A few weeks ago, my mother and I stood waiting in line outside Tia Sophia’s, a favorite breakfast spot in our hometown of Santa Fe, New Mexico. With several other New Mexican places in town, Tia’s is family owned and is a popular destination for both tourists and locals. Bursting forth from the door upon receiving a number in line, a young woman said to her friend, “Let’s go across the street to Henry and the Fish while we wait—they have great coffee.” I could see in the woman’s eyes the joy of showing her friend her “in,” secret spot in town, the friend likely visiting; I could also see that the woman had recently moved here.

Months before, my mother and I had walked the same section of street, marveling at the fact that hardly any of the businesses had been there when we first lived in Santa Fe, Henry and the Fish included. Moreover, this new crop of businesses seemed entirely alien to the culture of Santa Fe we had once known: designer clothes, smoothies, and yes, cutting-edge coffee enticed us from every stoop, but none of this seemed tailored to the population that actually lived in this city. Instead, Henry, the Fish, and its ilk seemed fashioned for wealthy outsiders, a population which would naturally replace those who had lived here before.

*

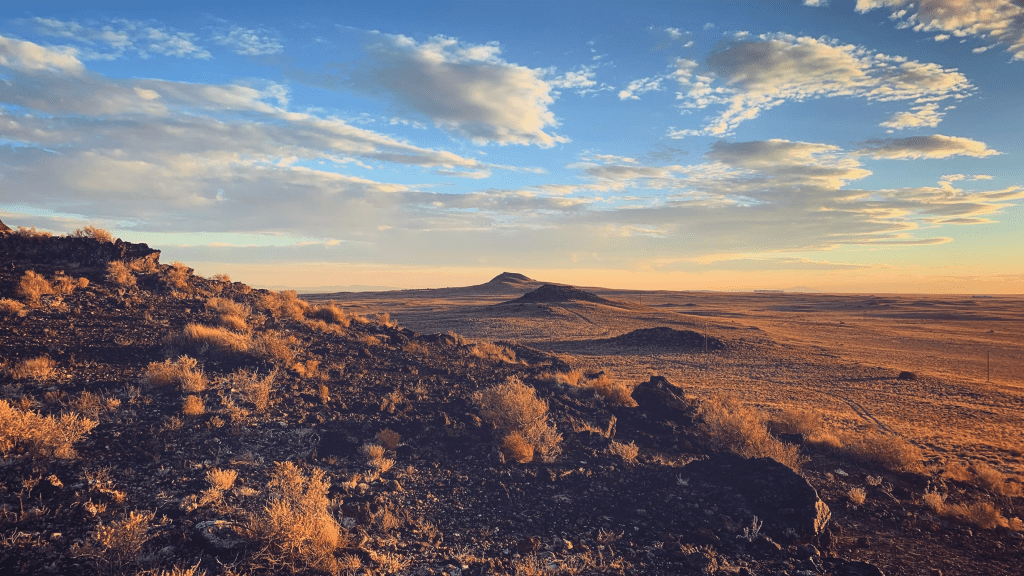

When I was growing up, Santa Fe, New Mexico seemed my and my parents’ little secret. Seatmates on planes frequently took double-takes and asked where in Mexico I had said I lived—Mexico, not New Mexico—and in high school I and my classmates were encouraged to write college essays on our home state, presenting admissions committees with exoticness.

This dynamic seemed to change around 2016, at which time Meow Wolf opened its internationally recognized House of Eternal Return. Even prior to the exhibition’s unveiling, Meow Wolf’s construction had meant a drove of young people suddenly moved to the city, shifting the demographics; once the site was in operation, it drew a new kind of tourist to the city, and I no longer felt that I lived in an “exotic” place.

By the Covid pandemic, at which time I had returned to Santa Fe after graduating from a Master’s program, I noticed that being a local itself had become “exotic:” when asking where I was from, Santa Fe inhabitants would often remark that it was “rare” to meet a local, or in one case the person even said, “Yeah right, nobody’s from here.” Suddenly, I was an anomaly merely for continuing to live where I had grown up.

*

It feels significant to this discussion what the House of Eternal Return is, the way in which Meow Wolf’s exhibit commercializes the culture I had always known in Santa Fe.

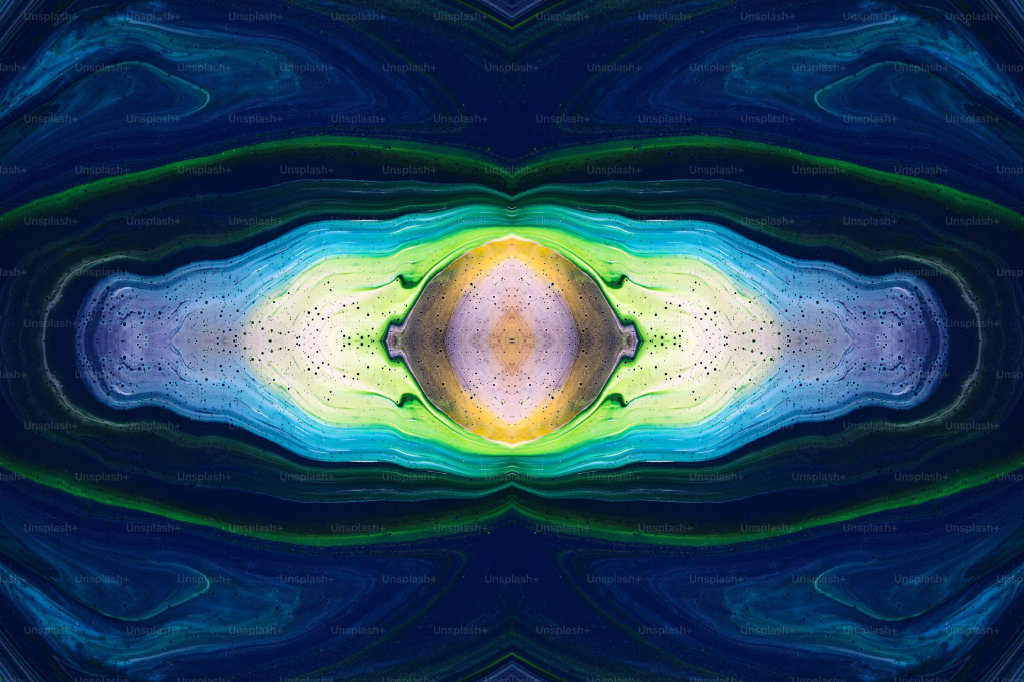

Entering the exhibit, patrons learn that something mysterious has happened in the titular, navigable “House:” there has been a cosmic event, and a focal family’s little boy has been lost in the multiverse. Analyzing paraphernalia in the exhibit, one can learn reams more about the backstory, such as the direction of the father’s experimentation, the origin of the machine he used to navigate the multiverse, etc.

More tangibly, one can enter the multiverse through a series of portals, most famous of which is an empty refrigerator. Through these portals, one encounters a pantheon of visually appetizing rooms, each of them the province of a local artist. Meow Wolf’s exhibit makes manifest a blending of new ageism and particle physics, a dreamscape through which patrons can walk.

Growing up in Santa Fe, this blend is precisely what I knew as my hometown’s culture. Just north of Santa Fe is Los Alamos, the site of the atom bomb’s construction as well as one of North America’s premier laboratories, and I was always aware of the rigor of scientific activity taking place here, in my vicinity; similarly, Santa Fe has always attracted people interested in the occult, and throughout my childhood it was not uncommon to hear talk of reincarnation, astrology, tarot, etc. Putting the two together and rendering them as a product, we get Meow Wolf, and the actual people I knew who trafficked in these ideologies feel but a memory.

*

And yet the same argument could be made about the ideologies I knew as “authentic” when growing up in Santa Fe, the same sort of Eternal Return.

Although new ageism felt like Santa Fe’s terra firma when I was a child, the ideology itself is an extrapolation of religious mythologies, an excavation of those mythologies’ cores and abstraction to pragmatism. In other words, reincarnation theory would not exist if not lifted from Hinduism; discussions of consciousness if not lifted from Buddhism; notions of the collective unconscious if not decontextualized from Jung, etc. To those who had prized the earlier, more pure forms of each of these ideologies, my family’s new age doctrines themselves must have felt like an alienating co-optation.

Similarly, it is easy for me now to decry newcomers to Santa Fe, claiming that they have supplanted my culture, but that is exactly how current inhabitants—many of them Hispanic—must have felt when I and my parents arrived in the 1980s from California. Equally, Native Americans must have felt that way about the Hispanic peoples who conquered them, and one could even imagine that the animals and trees who preexisted the Natives bemoaned the colonization of the latter, human drama tarnishing a formerly free and quiet landscape. And so on to the primordial stew.

*

In the moment when my mother and I awaited our breakfast, and the young woman emerged from Tia Sophia’s eagerly telling her friend of Henry and the Fish, I felt badly for her: I felt that what I had known growing up, she would never see, precisely because her arrival in Santa Fe had heralded its death.

And yet perhaps Meow Wolf’s House of Eternal Return itself stands as a metaphor for the ways of seeing which coexisted in this moment, the differing realities each of I and the woman beheld.

Just as to myself, Henry and the Fish is a perversion, an inauthentic surrogate for what might have stood on that same corner when I was growing up, to the woman it is a marker of Santa Fe’s novelty and promise, an exciting commodity she prizes for herself and chosen friends. And when that business one day goes under and is supplanted by something else, to that woman perhaps it will become a site of mourning, while to some newcomer even fresher than she the new business will become the prize, the oasis—each individual inhabiting their own vantage in the multiverse.

I miss the Santa Fe I knew growing up here, but I also know that at the time I couldn’t wait to leave, feeling stifled by the place’s smallness, its predominately older population. Now that Santa Fe seems to have been discovered in a new way and more young people have flooded the scene, who am I to denigrate the change, wishing for a past relegated to memory? My experience of Santa Fe’s change—indeed, of the city’s essence—is unique to the slice of time I occupied, the culture with which I resonated, and what I surmised of those experiences, a pointillist vantage no more nor less “authentic” than any other person’s.

What did that woman see that I could not, as she sized up Henry and the Fish?

Whatever it was, it lay through a door to the multiverse.